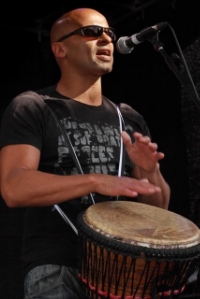

We spoke with Curtis Watt and learnt about his first poem, his upcoming work and his experience in drama school!

Can I have a brief introduction - your name, what you do and what you write?

Curtis Watt: My name is Curtis Watt, I am a writer, performer, actor and musician.

When did you start writing and what made you initially interested in writing?

CW: Well, the first poem I wrote was just before I turned 7. It was called ‘The Light of Life’. It went - ‘Life is nothing to worry about, once you die, your light is out//Most people worry about their lives…’ and I left it for two weeks to come up with the last line that didn't sound corny and then I said ‘…but some people live till 105’. I showed it to my mum – her face dropped, and I said “What's the matter, mum?”. She said she didn’t understand why I talked about death. I said “It's not about death, it's about life”. That's why now looking back, I think that I was just born as a writer because I left it 2 weeks to finish the poem. I didn't want it just to be any line, it had to make sense. I'm hoping to live till I’m a 105 by the way, wish me luck [laughs].

Do you write poetry or prose?

CW: I thought you said poetry operas! [laughs] I write both poetry and prose. I've got a book of riddle poems and nonsense poems and stuff like that, but I'm also working on quite a serious novel which I have been working on since 2011 - I've got about a chapter and a half left to finish. Lots of procrastination going on there because of too many different endings available.

Do you have a preference between hand-writing or typing?

CW: Well, I hand-write when I haven’t got access to anything else. When I've got ideas for things, I go into my iPad, go into notes and just note things down. It just makes it easily transferable but normally being a bit nerdy, I won't actually transfer it, I'll just rewrite it when I get on the actual computer.

How did you begin to first circulate your writing?

CW: Well, I went to drama school and then one day our tutor asked us to write a performance poem, so I wrote one. It was called ‘Bobby has a Big Belly’, but it was about Britain basically and sort of how people scoff a lot and don't really think of where it's come from, that kind of thing. So, it was quite political, wasn't that sophisticated, it was kind of funny at the same time. Also, we did our final panto in drama school - so I had to rewrite ‘You Can't Touch This’ to be the theme of pirates 'cause I was the bo’sun. I was the mayor and I was the bo’sun as well in ‘Dick Whittington’. And it was great because we had dancers there available and a live band playing ‘You Can’t Touch This’ and it was just amazing. It did get videoed but the video’s probably dilapidated by now. So that's where I would say I combined performing arts with writing. I joined the Liverpool Playhouse Youth Theatre when I was 15, and that was to stay out of trouble by the way 'cause I was in boarding school in Wales and then when I came back I'd be hanging out with my old friends who were getting on the lower tier of organised crime at the time, and my mum was the type of mum who would say, “If I catch you breaking the law or whatever, I will march you down to the police station myself”. So, I was having nightmares literally of being chased down by the police and stuff like that. Every time I came back, I was around these people 'cause it was very rural in Wales you know, so I was that kind of kid who loved nature and stuff. I just wandered down to the Everyman Theatre, there was no room at the inn, knocked on the Unity door, there was no room at the inn and then lo and behold (you’d think I was making this up!), the third place I went to was Liverpool Playhouse, I just knocked on the stage door and receptionist just said to me to put my name down, but the waiting list is six months. Then I went back to school and got a phone call or a letter from them saying I've been accepted into the youth theatre after 10 weeks because in those days, specially in communities like where I came from, lads didn't do youth theatre or any kind of theatre or anything like that. When I started doing it and when I’d come back, my friends would try to take the mickey out of me and going “I’ve heard you’re singing and dancing now”, as if that was something to be ashamed of. I’d just go “Yeah” and I said, “When you’re an actor, you've got to be an all-rounder and do a bit of everything” - I just left it left it at that. It definitely kept me out of trouble. My first workshop in Playhouse Youth Theatre, we had to do a (play where) I was with this woman, and she was supposed to be my wife in this thing and we would be obsessed with this TV drama about this doctor so I had to write the drama. (So) I was always wanting to write things as well as performing, so I just took that opportunity, it was a brilliant play, I think everybody did a brilliant job on that one. It was about people who were obsessed with things and we were obsessed with this guy and he was doing a ribbon cut and then we invited him round to our house, me and my wife, and then because he wanted to leave, we put his head down the toilet and drowned him. That was just an opportunity for me to practise writing because I was just obsessed with it. My mum wrote a novel about the Apache Plains Indians and then I burnt our flat down accidentally just by playing with fire - I've never slept much, so I used to get up when everybody else was asleep and I used to play with this little pen and put it in the fire and drip it onto paper to hear that little sound and then I’d stashed it behind the couch and in those days with woodchip wallpaper, they started making it with plastic instead of wood so the whole flat went up and then my mum lost her novel. It was all handwritten as well and she drew the characters from it too. So, I would have written anyway, but I feel like I sort of owed that to my mum’s legacy. I've got a book ‘Children's History of Liverpool’ but that was more of a commission - it wasn't really done the way I would have written it if it was all up to me, so I really want to honour my mother’s memory by being (a writer). Again, you got to be careful what you wish for because I was thinking well, by the time I’m 40, I want to be an author, but what I meant was a novelist so you got to be very specific about what you wish for. I've written a novel and like I said I have a chapter and a half to go.

Do you have a fanciful or pipeline piece of work that you want to write?

CW: Yeah. I had to teach myself grammar and punctuation because the good English teacher we ended up having (we had three while I was in that school) was unfortunately in our last year of school. She was actually an amazing teacher and a really good English teacher as well on top of that, but the two before that just didn't have any faith in the kids at all. So, when it came to colons and semicolons, I was eager to know how you break it all down but they never bothered doing that as it was A-level stuff. I didn’t understand why they couldn’t give us a little soupçon of what it entails – bad attitude.

How do you deal with writer’s block?

CW: I don't really have writer’s block. The only way I could describe writer’s block is when, for example, getting to the last chapter of this novel that I've been writing for years, it's more a case of – see, even Stephen King disappoints people with endings in most of his books and every now and then it's got an amazing ending, (my mum was a Stephen King fan, we all were in our house) and I think that's the difficult part for me, just ending things. Even Agatha Christie and most murder mysteries have terrible endings most of the time, so it's that - I think that's the only way I describe it 'cause I never think, “Oh, I don't know how to put this across” or anything like that, it's just more plot with me when it comes to writers’ block. It's only at the end of this particular novel, and I'm sure if I write another novel after that it will be the same thing.

How does writing express your thoughts more so than other medium?

CW: That’s a good question. There's one thing I try not to do is to talk too much about what I believe in or what bothers me just in everyday life because you just end up being a whinger. I think when you make something, a poem or a piece of prose or something, or even a joke - if you’re an artist(e) of any kind, that's how you express yourself because you were born that way or something happened to you that made you that way, and that's how I prefer to express myself unless it's an intimate conversation with somebody. When I'm talking to a larger amount of people or trying to express it on a broader level, I like to create an artistic way of putting that across.

What would you hope that your work would provide for people?

CW: I would just love to be sitting on a train (I don't love London but it's a long enough train ride to read a book or a novella or something) and see(ing) someone engrossed in your book. I would love to see that; I wouldn't even say anything unless someone seems up for a conversation and I might say sign it for them or something. But again, I don't know whether I would necessarily do that. One thing I don't like - if I do a poetry set or even a rap set – I don't want people to come up to me and say, “You were great” or “You were brilliant”, because I don't trust my own ego. I keep it sort of on a leash in the basement with a Hannibal Lector mask on. So, I don't want people to build up my ego because that means you’re at risk of becoming arrogant and lofty and I don't like people like that, it reminds me of ‘Animal Farm’ - you start off just a normal person and end up thinking you're better than people. I normally just disappear like Elvis (after my set), just going out the back door but sometimes I’ll maybe get one drink, listen to a few other people who were on and then make a very, very surreptitious exit out of the place 'cause I don't want anyone to build my ego up 'cause I might think I'm better than I am, and that means my art will lag. I’d rather have someone come up to me and say, “Oh you know when you did that poem, I've always thought that but not known how to express it”, or something along those lines, because it’s the poem that matters. I don't really want that kind of attention; I just want people to see themselves in it and be entertained by it. When I left drama school, I went to an amazing place called CADT (Centre for Arts Development and Training) - I think it still exists in a way but it's nothing like it used to be. It was like an add-on to whatever you did in college - that was amazing and it was a way of trying to make your artform into a vocation. And so, if I expect people to pay to listen to my poetry, it's like a chef in a restaurant or pizza delivery person – you don’t ask someone to come out the house and meet you halfway up the street, you got to deliver it to them and it's got to be what they've asked for or what they need even if they don't know they need it. That's how I looked at it, so I just thought I've got to work hard at it for this to be relatable to people.

What is one thing that you would say to your younger self as a writer?

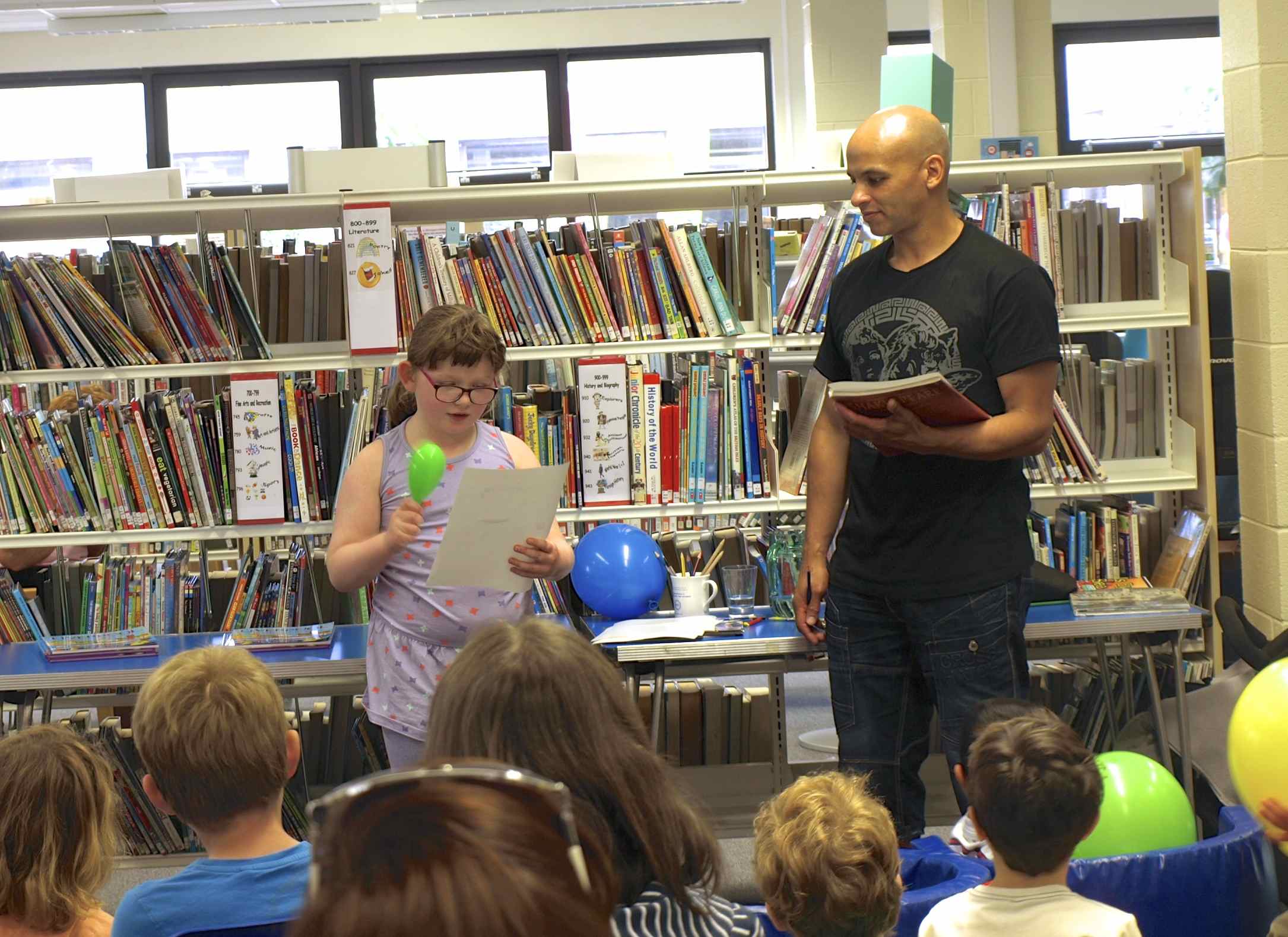

CW: I would say, “Wow, look at this Apple Mac computer you've got that’s dead easy to write on and gives you spell corrections”. If I could bring my 10-year-old self into this technological age, he would be amazed. And I've got one book that’s my book (Children’s History of Liverpool), but I’ve also got two of my poems in Michael Rosen’s ‘A to Z: The Best Children's Poetry from Agard to Zephaniah’ - one of them is called ‘The Death of a Bully’ and they only put the beginning of it (in the book) because either they didn't understand the story/narrative of it or they just didn’t have space and they only put the first page in which doesn't really do the poem justice as it's a poem with a twist at the end. I suppose they just did it because the book is aimed at a younger age, but I do it in primary schools all the time and the kids get it all the time. I would say it's good that (I’ve got poems in) Michael Rosen's book and I've got a book on my own even though I said it wasn't edited the way I would like it - I'm actually considering redoing ‘Children’s History of Liverpool’ the way I want when I finish the novel (I’ve already finished my new poetry book) 'cause when they’ve illustrated it, it's just not very multicultural with the images that they put in it. They didn't put any effort into that whatsoever and it makes me feel a bit embarrassed because I didn't do it and it looks like it was me that did that when it wasn't. That's the problem of monetizing your work, you’re sort of giving it to a surrogate in a way.

What is a piece of advice you heard when you were younger and that now you would pass on to like aspiring writers?

CW: When I was in Youth Theatre, there was a director called Morag Heard, her name’s Morag Murchison now, she was my favourite director in the Youth Theatre and she said to us all one day, “When you're acting, aim for the impossible. So, aim for about 120% because then the least you will get to will be 100%, 'cause you're aiming to do the impossible.” I suppose that's kind of driven me for my whole career really, when I'm doing things - just try and be your absolute best in things and in an impossible way and then you might land somewhere within the possibility of being what you're trying to be.