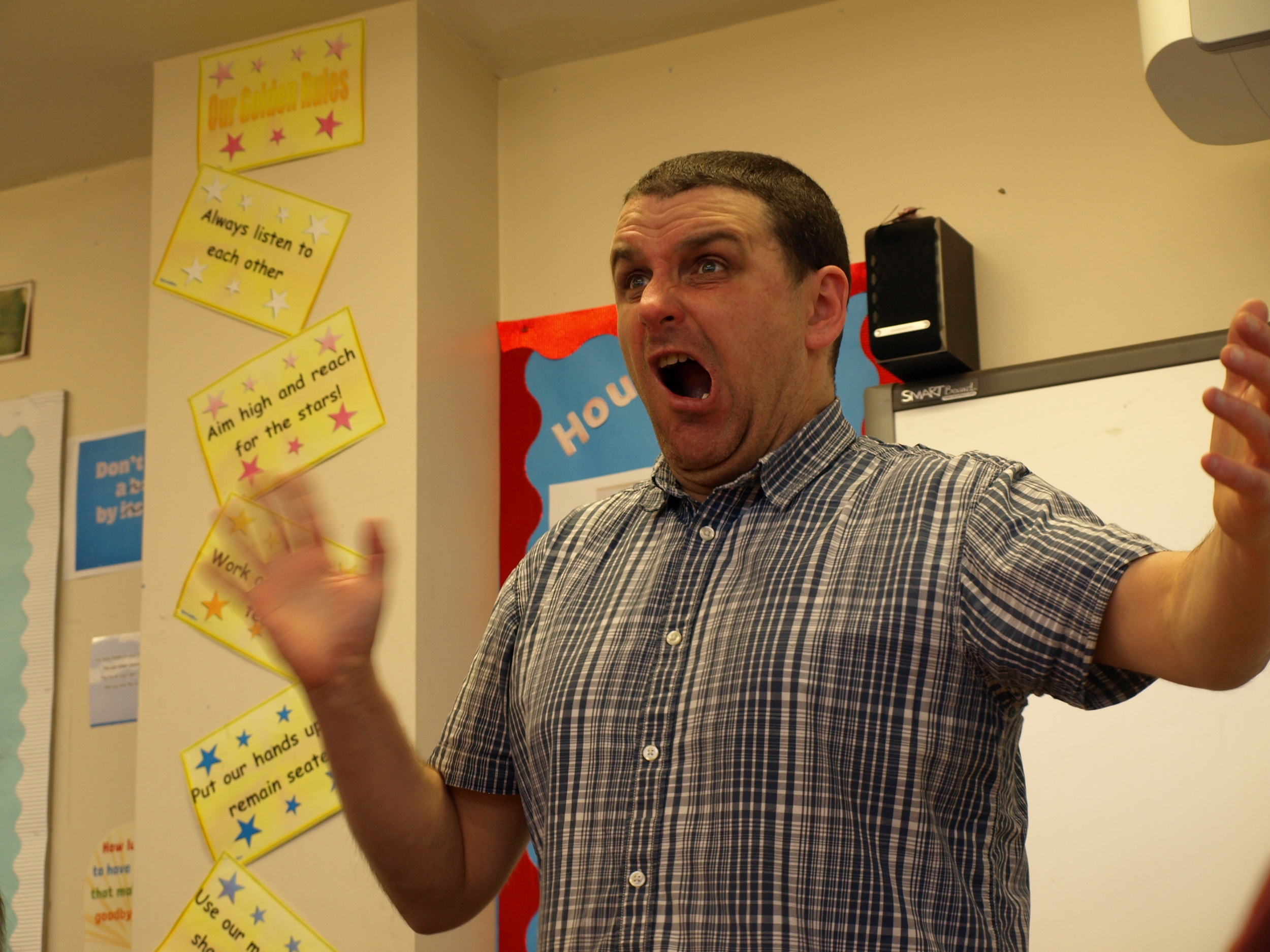

We sat down with John Hughes and found out more about his journey to writing for children, his upcoming work and his advice to aspiring writers!

Could we have a brief introduction?

John Hughes: My name is John Hughes. I’m a storyteller, a performance poet and occasional writer as well.

When did you start writing? What made you interested in writing?

JH: I’ve always written. At school, my favourite homework was to write a story. I realised I wanted to be a writer when I was writing stories and the teacher hadn’t told me to write a story, so I thought, “Ah, I want to write my own story,” and then I continued writing after school and everything as well. I think it took me a while to realise what kind of writer I am – I mean, now I see myself as a performing storyteller, performance poet for children, mainly, although I do a few bits for adults and young people older than children. That’s how I see myself now, but I think I spent a good few years wondering what type of writer I was and did some stand-up comedy, I did some performance poetry but then sometimes the talk was more entertaining than the poem, so I thought I’d do some stand-up comedy, and I think ever since then humour has always been at the heart of what I do. I think I found that I write funny stuff and tell funny stories and I perform funny poems, and I realise now that I like it to be quite interactive as well with the audience, I like kids joining in, I like them contributing ideas as I tell a story. So, I think it took me a while to realise that that’s what I wanted to do. I thought I was going to be serious author and all my serious author stuff was rubbish, it was terrible. And I always thought that anything I do with children, like with what I was doing with Windows, I thought that was a bit on the side, “Oh, I’ll do this on the side, meanwhile I’m trying to be a serious author,” and then I realised, “Actually, this Windows stuff, this storytelling stuff is great.” And then I got more and more into doing that and I realised that’s where I was naturally, that was my natural world if you like, was performing and telling stories with children in schools or in lots of other circumstances like festivals or you know, wherever, really.

Do you write poetry or prose? Do you prefer writing by hand or typing?

JH: Well, I write both – I’m working on ‘The Great Unfinished Novel’ at the moment, which is a children’s novel. And I like words on and off the page as well. So, the storytelling can sometimes be written and then told, but not too much in a way. Sometimes I like it to be a bit free with the audience, so kind of like stand-up comedy where you might kind of write but you still want to be very flexible with it in front of the audience on how they join in, on what they say. So, that’s sort of a prose way of writing.

When I do poems between the stories, they’re more written down, recited almost like songs. I think of them as modern nursery rhymes where you can join in, or like skipping songs – they’re quite contemporary but they owe a lot of earlier folklore, earlier nonsense rhymes, earlier nursery rhymes, etc. I like the idea of writing limericks, I do limerick workshops; I like the idea of doing kind of nursery rhyme workshops as well where there’s strict rules on how you write a poem, like where the rhyme should go, where the rhythm should go, but also you can let your imagination go wild. I like the discipline of the structures but also the wildness of the imagination.

I write these by hand. I scribble, I’m a great scribbler by hand. What I do now though (with the novel) is that I scribble a lot by hand, I surround myself with scribbles, I take photographs with the iPhone, which is something I wouldn’t have had years ago when I first started writing, so I now take photographs of my scribbles and then I type up my notes on my phone sometimes. So, when I’m travelling on the train to, for example, Plymouth, to do some storytelling, I’ll think, “Oh, I might as well look at these scribbly notes that I’ve got photographs of and then type them up.” And then they become something that can be typed again and again, and then there’s the laptop as well. Scribbling is definitely at the heart of it – I think I like the instinct of a scribble, I think of little ideas and scribble them down quickly. I write little bits as well. I do storytelling and poetry, but sometimes I do little rhymes. So, somebody from the audience might say, “My name is Ted,” and I go, “Oh, I know someone called Ted, who lives in a house made of bread. He had a bad feeling, when eating the ceiling, the toilet fell onto his head.” I’ve just got these little bits that I can throw in and make a rhyme out of somebody’s name. I tend to do those when it suddenly occurs to me on the bus, so I scribble it down, but now as I said, I take a photograph of it as well.

Do you have a fanciful/pipeline piece of work that you want to write?

JH: I think I got sidetracked from my writing to do storytelling and performing because that became a more regular thing. And anything else I wanted to write, I didn’t really have the time – I do a day job as well, I work in Tate Liverpool. Any writer will tell you, “Where do you get the time?” Lots of people say, “I’m writing a book”. Peter Cook apparently once said to someone at a party, years and years ago in the 1960s, “What do you do?” and this person said, “Oh, I’m writing a book” and Peter Cook said, “Neither am I.” Because, a lot of us say we’re writing a book but we don’t really get on with it. So, it is the real discipline of having to get on with it. This book (that I’m writing) is a funny book and humour takes time. Although humour is kind of wild and wacky, but it’s also the most precise writing as well, you want it to land, when someone reads it, you want the words to land in a certain way so that it creates a humorous response, either laughter or just an inward chuckle or something. I think humour is the most disciplined way of writing because you have to cut out any bits that aren’t funny, it can sound too forced if you’re pushing the humour too much, so you get rid of a lot, you edit a lot. So, working on the novel, the working title at the moment, we’ll see whether this happens in the next few years, is ‘Jimbo’s Nose and the Shapeshifting Onions from Planet Puh-ding’ and it’s all about these onions that can change shapes, they can become that chair or this table [points], they can blend in – but it can run around, so that table can run around. But because Jimbo’s nosey, he discovers that this is going on. I hope that it might be, as you say there’s these fantastical ideas of things that you want to write, I would like it to be part of a series of novels about Jimbo and his nosiness. So, ‘Jimbo’s Nose and the…’ would be a series of novels. That’s kind of an idea I am fostering at the moment, we’ll see. Even on the way here, I was looking at it on my phone and making mental edits. I’m such a fussy writer, people say, “Haven’t you finished that novel yet?” and I’m so fussy, I just go, “That just needs a bit of work, that just needs a bit of work” [pointing] and a lot of people tell me to just get on with it and get it out there. Maybe that’s what I should do.

How do you deal with writer’s block?

JH: I think sometimes the answer to writer’s block is to just write anyway, kind of scribble (for me anyway). Lots of people have different ways of dealing with writer’s block. I just scribble anyway. That can be a bit dangerous though because you just scribble and convince yourself you’ve done something good when it might not be that good. So, scribbling without an idea is a bit like a guitarist writing a song without an idea (sometimes they have an idea and play it on the guitar) – my friend who’s a musician once told me when you do that, you’re playing with your hands rather than playing with your ears. If you’ve got a tune in your ears, you can kind of imagine it playing with your ears. If you play with your hands, your fingers fall into certain places that you’re comfortable in – so if you’re comfortable playing a D chord and an A chord, you just pick up a guitar and do that. I think that’s the same with scribbling; sometimes, you can get into a habit of scribbling certain things, and it might not be that helpful. But I do also think that when I get going, I’ve scribbled so much, say I’ve done two pages of scribble, but that bit on the end of the second page is where I’m finding my feet now. I’ll get rid of all that other bit, and people will say, “Oh, isn’t that really terrible to get rid of all that stuff that you’ve written, isn’t that really heartbreaking to get rid of all this material?” I go, “No, because all that stuff helped me find this little bit here and now, I know what I’m doing with this little bit here.” If that makes sense.

How does writing express your thoughts more so than other mediums?

JH: I think, especially doing workshops with children and young people – because a lot of stuff is wacky and funny, and sometimes I wonder about me, I think I had a teenage phase and maybe a phase in my 20s where I did write about me and my thoughts, whereas now, even when I write ‘I’ and ‘me’ in my performance poems, it’s normally from a point of view of a child that isn’t me. When I work with children in workshops, I do think it’s a great way of looking through your inner thoughts and ideas, whether they’re just fantastical ideas, or whether they’re things that need addressing in your life, whether there are difficult things going on in your life. I think the whole world of storytelling and poetry are often a way of dealing with dark (thoughts/themes). Some fairytales are quite dark, or difficult, and sometimes, when dealing with difficult things in life, poetry, stories, art in general, music, I think dealing with things in a creative way is always a beneficial, positive thing. Even things that aren’t positive in life can be dealt with positively through creativity. Sometimes, it’s a way of articulating to yourself what’s going on, in a way – by telling others, you’re telling yourself as well. I think that’s what writing is. Writing is about articulating things, it’s about getting the right words in the right order and go, “Ah, that’s what I mean to say,” whether it’s about me, whether it’s a child trying to say something about themselves, or about their friends, or their group or their identity, or whatever it might be. I think writing is a way of telling others, and when you’re telling others you’re also telling yourself, something and there’s lots of ways of doing that – stories, poems, songs. You kind of have a wally idea of something, and writing makes it precise. But I don’t want to rob writing of its mystery either. Writing can create more confusion in a way, and sometimes it’s nice to confuse your audience, to make people think of weird things or think in a weird way as well. So, sometimes it’s a way of going, “Yes, this is what we’re writing about and now we’re done with it and it’s writing”, sometimes you’re just exploring it and you might not deal with it, but that’s just as valuable. We don’t always need definite answers to everything. Creativity can raise questions as well as answer questions.

What would you hope your work provides for other people?

JH: As I’ve got older, I think more and more about audiences. Writing this novel, for example, I work a lot with children so the main character in my novel, he describes himself as ‘nearly 11 years old’, that’s how he describes his age. I’ve worked with a lot of people who are 10 and describe themselves as nearly 11. So, when I think of that audience, I don’t think of them as an abstract audience, I see the whites of their eyes quite a lot. I sit in a classroom or a school assembly and there they all are, a big audience, and when I think of that audience, or when I think of them with their teacher and how they work together, or when I think of them with their families, with their parents or carers, I always think, “Oh, yeah, I want this book to work with them.” I always think about the audience and I kind of think I know the audience. I think I’m imagining the audience. When I used to write for grown-ups, I used to have a vague, abstract idea of who’s reading the novel, whereas I’ve got a more certain idea of who’s reading the novel when I’m writing this book. Also, when I think of my stories and poems, they are going to be performed and it’s great because one of my well-known poems is ‘Grandad’s Beard is Weird’ and I think that started out as a longer poem, it was only seeing what worked and seeing what didn’t with the audience, not me thinking what was better or good but looking at the audience and going, “Ah, they really like that bit, that bit’s really funny, I’ll keep that bit. They’re all looking at me funny during that bit, so maybe I’ll leave that bit out.” So, now it’s a nice punchy piece. It’s great because you’re always meeting your audience and writing rather than trying to imagine your audience and writing.

What is one thing you would say to your younger self?

JH: I would tell my younger self to lighten up a bit, maybe? Because I think I thought of myself, in my late teens, when I first got involved with Windows actually, back in the 80s around ’87-’88, a long time ago, ancient history – many many centuries ago [laughs], as a voice of the working-class youth and I wrote in a very Liverpool, working-class way, a very angry, young way. I thought I was radical and young and there’s some stories and poems in SMOKE magazine when I wrote under the name John Baron years ago, because my middle name is Baron and my full name is John Baron Hughes and I used to knock the Hughes off – again, I would say “Lighten up, John! Stop trying to think of a funny name, just use your normal name!” I think when I found the comedy, that’s when I wished I’d found that a bit earlier because I never thought of comedy, when I was young, as being central to what I was doing. It was everywhere else in my life and I thought, “Why don’t you use this being funny thing in your writing and your creativity rather than trying to exclude it? Like, oh I’m being funny over here with my mates and then oh, I’m writing now I’m being very serious.” So, I would say bring that world of my mates into the writing, the fun into my writing. Bring the fun into it.

One piece of advice you heard that has stayed with you until today, and you would want young writers to know?

JH: I think when I first went to schools with Dave Calder, sadly miss Dave Calder who used to run Windows with Dave Ward - I was quite young when I first went to schools with Dave Calder, and I still felt like a sixth-former and I wasn’t particularly brilliant at school, and I felt nervous about going back to school because I thought people who work in school are clever and I was just one of those pupils and suddenly I thought, “Why am I working in a school? I’m just one of the pupils who can’t wait to get out of school.” And then, Dave Calder said, “Don’t worry, you’ll be fine”, typical Dave Calder [laughs] – and it was fine as soon as I told myself not to worry, and that it’ll be fine. I think people sometimes worry about their creativity or worry about what they’re doing, and I would say don’t worry, just do it. Obviously, you need to worry to a certain extent, you need to be concerned about what you’re writing, you want to make it good, you want to edit it. I think it’s good to worry in a healthy way or be nervous in a healthy way about what you’re doing. People always ask, “Are you nervous when you perform?” and I always say, “Well, I’m nervous enough” – you can’t too relaxed, otherwise you won’t give it a lot, but you also can’t be nervous to the point where you’re like, “Aaaah” [shakes fists]. That’s the same with writing as well, you kind of want to be concerned enough with it to do a good job, but you don’t want to get so nervous to the point where you become unable to get on with it.

I would say, “Don’t worry.” Dave Calder told me not to worry years ago. I would say, “Don’t worry, get on with it. Be concerned, but don’t worry and don’t panic.” Sometimes people scribble on a piece of paper and throw it across the room, the frustrated writer, and I’d say don’t worry about that because that can be a bit negative and you’ll never get anywhere and you’ll have a bad opinion of yourself when you get like that. Don’t worry, be happy!